Flowers for Zora

Written April 2021

Edited July 2025

Zora Neale Hurston gave us the most. Her contributions to anthropology, sociology, linguistics, dance, ethnomusicology, womanism, and phenomenology are tremendous. Despite her illuminating the ways that Black folks express the fullness and multiplicity of God, she died poor without her flowers. Her grave sat unattended until Alice Walker found, cleaned, and beautified it. In the words of Walker, “In order to show people how beautiful they are, you have to show them how ugly they’ve been acting” (Walker 00:48:55-00:49:02). Hurston did that for us.

When I read “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” I come away in awe of Hurston’s articulation of the fullness and movement of God that finds expression through us. I glean the ways that our perpetuation of hierarchical dichotomous systems is incompatible with appreciating the beauty in the multiplicity of God’s creativity and expression. By placing Black life, experience, and culture at the center of her analysis, Hurston holds up a mirror to society, reflecting not only that which is lost under systems of subjugation, but more importantly, the aspects of natural wisdom that have been retained and continue finding expression through those who will not willingly be subjugated. Hurston’s work suggests that despite numerous assaults to Black people’s humanity, there remains a certain attunement to the divine, which will not allow humanity to exist harmoniously while subjugating relations are in place. “We merely go with nature rather than against it” (88) is to say that subjugation is not, in fact, natural.

In identifying characteristics of Black expression, Hurston calls attention to aspects of God which are observable in nature. These include, but are not limited to nonlinearity, rhythmicity, transformation, originality and mimicry, relationality and relativity, and multiplicity. She locates these aspects in Black folks’ art, performance, language, philosophy, religion, and social practices. Hurston’s elucidation of the characteristic of angularity conveys the idea that nonlinearity is a guiding principle in Black expression. She writes:

. . .the next most striking manifestation of the Negro is Angularity. Everything that he touches becomes angular. In all African sculpture and doctrine of any sort we find the same thing. Anyone watching Negro dancers will be struck by the same phenomenon. Every posture is another angle. Pleasing, yes. But an effect achieved by the very means which an European strives to avoid” (83).

She then provides an example of this angularity in home decor, noting how pictures are hung and furniture is organized to avoid “the simple straight line” (83). I am reminded of the times I have observed angularity in Black Dance. Ballet’s concern with creating lines is altogether absent from neo-traditional West African dance and African Diasporic dance. When I do Black Dance, I am moving various parts of my body at once, and straight lines and rigidity are the opposite of the ideal.

In a journal reflection of a dance class I took in 2018 with Moustapha Bangoura, I noted that Bangoura emphasized that no part of the body is stiff during African dance, specifically not the torso or core. I also recently participated in a “Somatic Practices for Healing Trauma” workshop, hosted by the California Institute of Integral Studies and facilitated by somatic psychotherapist Manuela Mischke-Reeds. During one of the movement exercises, my soma called for fluidity in my midline. From my root to my crown, from my pelvic floor through my core and torso, and on up to the top of my head, there is no stiff line to be found in the ways my body wants to move. My stability comes from fluidity, from the ability to create not lines, but rather angles and curves.

Accordingly, I’d like to add curvature to Hurston’s emphasis on angularity. And what are curves but ways around and angles but different vantage points to see? If my years on this earth and the wisdom of multiple lifetimes have taught me nothing else, I have certainly learned that I have to find ways around and ways to see in order to be my free, fullest Self. To “avoid the simple straight line” (83) is to be attuned to the nonlinearity of the divine and the fact that we are reflections of it. In my curvature and angularity, I am mirroring nature. I am expressing the ways that I, in this body, mirror God.

In conversation with Ra Malika Imhotep and Dr. Darieck Scott, Walker says, “Everything in nature just is what it is, and so are we” (00:59:50-00:59:54), and she highlights the necessity of circles and how our beauty mirrors that of the Universe (1:00:34-1:03:05). What phenomenon do you know in nature that is linear? The astrological chart is a circle, and charts are interpreted according to the angles planets create in relation to one another. Similarly, numerology orders numerical energies in a circle, thus creating angular relationships. Even seasons are ever-flowing in a cyclical fashion.

One of the greatest revelations from the Winter season is that not even trees know linearity. The trunk is not growing straight up; it is branching off and forming angles endlessly. My observation of bare branches imparted the knowledge that a tree’s bulbous shape is created by angles. My godfather, rest his soul, once told me “Life does not get harder. It gets broader, and you have to grow with it.” That is, I have to have angles to expand. Consideration of life experience will show us that we are nonlinear. I cannot count the number of times that I have come back around to the same lesson and found myself approaching the matter from a different perspective due to experience gained at previous times.

Hurston highlights that everything we create must be a reflection of nature and experience in order to inspire and move: “When sculpture, painting, acting, dancing, literature neither reflect nor suggest anything in nature or human experience, we turn away with a dull wonder in our hearts at why the thing was done” (Hurston 87). What comes to mind here is that familiar axiom, as above, so below. The continual reciprocity between the spiritual and material planes is a marked quality of life. When Hurston writes, “The Negro is not a Christian really. The primitive gods are not deities of subtle inner reflection; they are hardworking bodies who serve their devotees just as laboriously as the suppliant serves them,” (87), she is talking about spirit-matter reciprocity, a metaphysical understanding foundational to Black spiritual systems and ways of being. Akasha Gloria Hull elaborates on this continual process of exchange:

As human beings, having experience is the only way that we gradually learn and/or remember who we really, essentially are. . .

If one imagines a spirit-matter continuum with spirit at the top and matter at the bottom, then the journey proceeds from that high, topmost place all the way through to the lowest place before it reverses itself, ultimately completing what has been from the very beginning a return trip home. Along the way, everything touched by the energy of spirit is pushed to its furthest growth and potential -- wherever it is on its own spirit-matter path. . . Whatever or whoever embarks on this journey is always on the eventual way up even headed down. And this process is at work at every level, in each little experience or relationship, each lifetime (175).

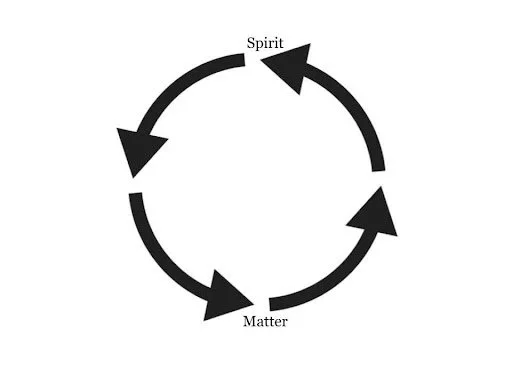

Hull’s continuum is circular, not linear; it is only in a circle that we could be simultaneously headed up and down:

With Hull’s conception of the continuum having spirit at the top and matter at the bottom, the above image is what that spirit-matter continuum would look like. However, in the vein of the Kongo cosmogram, I have imagined the spirit-matter continuum in the following way:

Either way, what is evident is the continuous flow of energy between the material and spiritual planes that Hurston posits is characteristic of Black folks’ religion. When she says that Black folks are not really Christian, she’s implying that Black folks’ have modified Christianity through the incorporation of Africanist elements, like the understanding and embodiment of the spiritual-material exchange. Across the Diaspora, Spirit is integral to all other aspects of life. It is not compartmentalized and reserved for certain spaces and places. When I say that I have an eye to the Spirit in all things, I am talking about this lack of compartmentalization. Every human experience for me is a spiritual experience, and I am experiencing Spirit through my material body. How could they be separate? How could they not be constantly in conversation and flow? Our tradition of ancestor veneration and communication with the Spirit world is a testament to this continuous exchange. We know that death is not an end, but merely a transition. It can only be a transition because we are not linear.

Through conversation with my sister-friend, Sara Makeba, I have gained greater understanding of the ways that white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism rely on the myth of linearity, lending credence to my belief that none of these oppressive systems are based on anything in nature. And so, as Hurston so aptly put it, I turn away with a dull wonder at why they were even created. Sara sent me a voice note with her theory that embracing nonlinear time makes a good case for ethical non-monogamy. She says that patriarchy, the foundation of rigid monogamy and relationship models, goes hand-in-hand with the concept of linear time. It is only a belief in linearity that could lead one to the fallacy that we’re able to control time or anything and anyone outside of ourselves. Expecting relationship permanence and considering all relationships that don’t last forever as failures are manifestations of this linear time fallacy.

So it is that recognizing and embracing our nonlinearity helps diminish these notions of permanence and control. Rather than seeking long-term monogamous partnership for the sake of longevity and monogamy, we might consider aligned partnerships and be okay with releasing what isn’t aligned. We might not insist on a patriarchal monogamous relationship model that is antithetical to how expansive we are. We might recognize that our love and care is not scarce and doesn’t have to be reserved for one person at a time until the end of time. We might express our abundance and participate in as many aligned relationships as we want to and for however long they feel aligned (Daise).

Since this conversation, the linearity inherent to white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism is all too glaring. The lack of curvature means that we’re not supposed to have ways around rigid states of being. The lack of angularity means we’re not supposed to see any other way or reality than the one that oppressive systems hand to us. A belief in linearity builds identities around what one is not, i.e., the dual hierarchies of white and Other, penis and Other, man and Other, etc. A belief in linearity allows one to draw a straight line from anatomy to gender, from womanhood to motherhood, from race to superiority, from capital to control. A belief in linearity allows us to ravage one of our most supreme mothers, Earth, and not consider the impact on human existence. To think that death is an end and not a transition is to have no understanding of spiritual-material reciprocity and multidimensionality.

Oppressive systems have been and still are ideological and psychological warfare about the shape of God, time, and life. But we know. We can look to ancient and indigenous philosophies to see that nonlinearity is the way and the truth, and we can look inside of ourselves to see that we are nonlinear. Acknowledging nonlinearity is heeding the wisdom Octavia Butler shared with us: God is change (3). Change is ongoing, and therefore so are we. Hurston located this ongoingness in our folklore. The beauty and genius of oral tradition is the dynamism that allows stories to become what they need to be in any given moment. Tethers to the past don’t imply a fixed quality, but rather a generative source from which present and future flow. Conversely, the present and future shape and transform the past. The trickster is at once Elegba, Anansi, Brer Rabbit, the Signifyin’ Monkey, and High John the Conqueror. As Hurston eloquently states, “Negro folklore is not a thing of the past. It is still in the making. Its great variety shows the adaptability of the black man: nothing is too old or too new, domestic or foreign, high or low, for his use. God and the Devil are paired. . .” (84).

The stories our elders tell us are not without purpose nor fixed in time. When I’ve sat on the porch with my Grandma and Papa, and when I used to visit or call my godfather, I’ve always known that their stories held revelations about their lived experiences that are relevant to me. And the story is never linear. There are tangents and nuggets of wisdom woven throughout that I would miss if I were trying to hear it in a linear way. Listening to Black elders’ stories is fine-tuning one’s ear to the curvature, angularity, spiritual-material reciprocity, and ever-flowing change of life. If I were listening in a linear way, I’d only hear what they went through and not what they went around. In linearity, I’d miss the perspective and the pairing of God and the Devil. I’d miss the divination in their words; their on, with, and in time messages for me directly from Spirit. I’d miss them telling me the ways that Spirit is intertwined with their material lives and the ways that they themselves are expressing God, time, and change. I’d miss the fact that my life flows from theirs. That’s a ton of wisdom to miss. I am grateful to Hurston for making it clear that we are nonlinear and ongoing. I am grateful for an expansive Blackness.

“Characteristics of Negro Expression” may not fall within the canon of Afrofuturism, but there are elements of the framework nestled within Hurston’s text. Ensuring the survival of the tools of the past and, therefore survival into the future, requires reaching across and through time to retrieve and adapt the technologies necessary for living in the present. Black folks’ living and survival is the fine-tuned art of two complementary technologies interacting: rhythm and improvisation. Hurston calls attention to asymmetry, not rhythm: “The abrupt and unexpected changes. The frequent change of key and time. . .” (83-84). However, she illustrates that asymmetry and rhythm are intertwined, and both are required for an assembled whole:

The presence of rhythm and lack of symmetry are paradoxical, but there they are. Both are present to a marked degree. There is always rhythm, but it is the rhythm of segments. Each unit has a rhythm of its own, but when the whole is assembled it is lacking in symmetry. But easily workable to a Negro who is accustomed to the break in going from one part to another, so that he adjusts himself to the new tempo (84).

I think about rhythm consciousness with respect to Black life, particularly the lives of ancestors and those of us in the present, existing in hostile environments characterized by ontologies that oppose natural rhythms. Whether it is heart beat, amniotic sac, menstrual cycle, ocean tides, lunar cycle, seasons, or day and night, rhythm is ever-present, and there are many rhythms at once. What happens when the abrupt and unexpected changes occur? We improvise. We find a pocket of time in which our improvisation can fit. We create a new rhythm. And in that new rhythm, we find the pockets of time in which more improvisation occurs. We are constantly adjusting ourselves to new tempos and new rhythms. We are constantly moving with a continuous flow even with the break in the rhythm.

In neo-traditional West African drum and dance, one of the features of the music and movement is the break, the drummed cue to change. A skilled drummer knows what pocket of time to jump into to play the break without disrupting the rhythm and knows how to use to adjust tempo and to transition. A skilled dancer knows how to change her movement when she hears the break and knows that a break is coming even if she can’t anticipate when. She knows how to improvise in the rhythm, and her ability to improvise depends on having a firm grasp of the rhythm and the pocket. Drummer and dancer communicate with one another. Either can adjust the tempo or challenge the other to find the pocket and bring something new. And it all happens continuously, no disruptions, just flow and deep listening.

Improvisation allows the asymmetry to emerge. What is Black living but the continuous flux of rhythm and improvisation? Our history is rhythm in segments. Our distinct identities across the Diaspora are rhythm in segments. Our survival has always depended on being in the rhythm, improvising, and creating a new rhythm. We do so by time traveling, by reaching across and through time for the tools necessary to maintain and adjust. Our travel is the evidence of our nonlinearity.

Music and dance originating within Black American culture exemplifies our use of these technologies and indicates our high level of attunement to the shape of God. Not lines, but curves: ways around the limitations and flowing with the changes. Not lines, but angles: ways of seeing the multiplicity and turning it into a whole. Not assimilation, but transculturation: maintaining the rhythm and adapting to new rhythms with improvisation, making something new with what’s available. We did that with the spirituals and the gospel, the blues and the jazz, the soul and the funk, the R&B, the hip-hop, and the trap. We did that with the Ring Shout and the Juba, the Cakewalk and the Lindy Hop, the Charleston and the Twist, the Wop and the Running Man, the Chicken Head and the Pool Palace, and every Crank Dat, line dance, and steppin song you can imagine. In the community circles and on the concert stages, Black music and dance are a testament to us knowing rhythm and improvisation to be two sides of the same coin. The one does not exist without the other.

And from the adaptability necessary to keep rhythm and improvisation in balance also flows the arts of originality and mimicry, again two sides of the same coin. Adaptability is a core element of the transculturation process and a marked quality of Black life, society, culture, and expression. Adaptability allowed our ancestors to bring Africa to America, adopt elements of white and indigenous American cultures, create a distinct identity, and transform American culture itself. The exchange and re-exchange implicit to our ways of being and expressing have allowed us to fine-tune the arts of originality and mimicry and recognize their flux in the balance of rhythm and improv.

On originality, Hurston writes:

What we really mean by originality is the modification of ideas. . . the Negro is a very original being. While he lives and moves in the midst of white civilization, everything that he touches is re-interpreted for his own use. . . Everyone is so familiar with the Negro’s modification of the whites’ musical instruments, so that his interpretation has been adopted by the white man himself and then re-interpreted. . .Thus has arisen a new art in the civilized world, and thus has our so-called civilization come. The exchange and re-exchange of ideas between groups (86).

And on mimicry, she says:

The Negro, the world over, is famous as a mimic. But this in no way damages his standing as an original. Mimicry is an art in itself. If it is not, then all art must fall by the same blow that strikes it down. . . He does it as the mockingbird does it, for the love of it, and not because he wishes to be like the one imitated (87).

This is attunement to the divine laws of change and exchange. This is the delicate balance and flux of complementary forces, of giving and receiving, of reciprocity. This is an indication of the subjectivity inherent to human experience, an indication of you can take my body and expression out of Africa, but you cannot take Africa out of my body and my expression. You can try to violently dislodge it and impose upon it, but you yourself will become influenced by it. I am nonlinear. I am multidimensional. I exist across multiple worlds at once. I excel at imitation and at originality. A break in my rhythm is a pocket for change, improvisation, and a new rhythm. I create a new rhythm out of mimicry and originality. I just create. And you feel it.

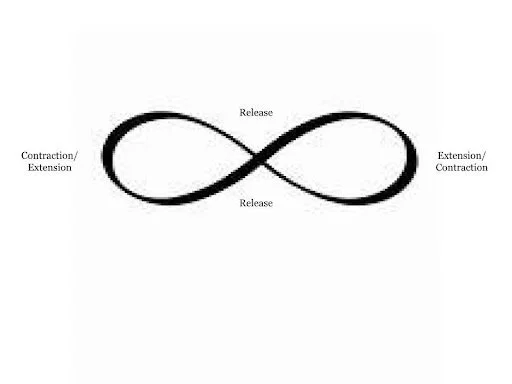

They feel it because we are suggestive, not explicit in our let me show my way. We don’t impose our culture, and yet it is received and integrated into the mainstream. We let divine flow do its work of balancing. We are forever flowing through the contraction-release-extension continuum, a continuum of curves and angles, of going around this society’s proscriptions and of seeing from different perspectives in order to show up as our multidimensional, nonlinear selves.

In Hurston’s description of Black Dance, she illuminates its suggestive nature:

Negro dancing is dynamic suggestion. . .It is compelling insinuation. That is the very reason the spectator is held so rapt. He is participating in the performance himself -- carrying out the suggestions of the performer.

The difference in the two arts is this: the white dancer attempts to express fully; the Negro dancer is restrained, but succeeds in gripping the beholder by forcing him to finish the action the performer suggests. Since no art can ever express all the variations conceivable, the Negro must be considered the greater artist, his dancing is realistic suggestion, and that is about all a great artist can do (84).

As I was writing my Master of Arts thesis in 2019, I worked a lot with Dana Mill’s theory of dance as its own method of inscription, functioning through contraction-and-release (9). Mills’ work corresponds with Hurston’s assertion that Black Dance (and by concomitance, Black music, since music and dance are not separate in Africana cultures) is a suggestive art. I expanded on the contraction-release model by adding a third space, extension, and the continuum became an infinity shape. Contraction and extension both function as spaces of tension; first- and third-person perception of our moving bodies are always in conversation with one another and mediated by a space of equilibrium, the release. This continuum rounded out my theory of neo-traditional West African dance as a somatic movement practice for Black women in the United States.

Black folks’ living and expressing, including but not limited to dance and music, is constant travel along this continuum, at once considering how we experience ourselves and how we are perceived by others; at once concerned with self-definition and self-assertion and how oppressive framing has defined us and told us we can express; at once contracting into our pasts and extending our lives into the future; at once calling on ancestral wisdom and integrating unfamiliar aspects into our ways of being; at once integrating the ways of being within us and the ways of doing necessitated by an oppressive environment. When Hurston talks about Black expression, she shows us the ways that our expression is a release point where multiple worlds, multiple stories, multiple ways around, and multiple perspectives converge. When I talk about the Africa within us, I am not talking about some static, monolithic, romanticized conception of Africa. I am talking about the dynamism, the multiplicity, the adaptability, the ongoingness. I am talking about the divine and our attunement to it.

And so is Hurston. The Africa within us survives and continues to be expressed, no matter where we are, because of the inclusive-integrative principle (Hazzard-Donald, 40). We and our traditions survive because we are adaptable and open to integrating elements that allow transformation to take place. Rigid structures do not stand. They collapse by the force of the elements surrounding them. Fluidity is a must for anything to survive. Whatever we have to work with becomes useful and suited to our needs and purposes. We always have ourselves and our embodiment, and we always have whatever is given to us by whatever environment we are situated in. Again, “nothing is too old or new, domestic or foreign, high or low for his use” (Hurston 84). It takes curvature and angularity to make use out of what is available. It takes recognition of the nonlinearity and multidimensionality inherent to our being. It takes rhythm-consciousness and improvisation.

And what is the infinity symbol but a circle that is twisted in on itself, maintaining the outer curves while reducing the inner angles? Our existence in this white supremacist patriarchal capitalist environment is maintaining ways around while having to reduce ways to see inside, hovering between our objectification and our subjectivity. Yet, the full 360 degrees is still there. The angles outside of are the wider angles, making the points meet so that we are expressing the fullness, still ongoing, still cyclical, still nonlinear, still whole.

The question I am left with is, when do we get to twist back out? When do we get to express our infiniteness and nonlinearity without having to twist in on ourselves? When does my full 360 self not require having to see myself through the white, patriarchal, capitalist gaze? I believe it’s when I can recognize Spirit’s role in the whole thing. Returning to the circle is the recognition of Spirit, when I can use that spiritual-material reciprocity to untwist myself and expand back out into the circle where my curves and angles are wide and still present, but not limited by forces created in my opposition. And so it is that we are untwisting and finding the fullness of the circle, its angles, and its curves.

May we continue finding the nonlinearity, the angularity, and the curvature, within our movement and expression. May we continue finding the rhythm and improvising in the pocket. May we continue using the arts of originality and mimicry for the maintenance and production of these rhythms and improvisations. And may we find our way back to the circle. We are nonlinear. We are multidimensional. We are material and spiritual. And may we never forget that. May we never forget that we are God’s mirrors. And may we always be grateful to Hurston for seeing that beauty and reflecting it back to us in her work. Ase.

Works Cited

Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Sower. Grand Central Publishing, 1993.

Daise, Sara Makeba. “Pt. 2.” M4A file, created 8 March 2021.

Hull, Akasha Gloria. Soul Talk: The New Spirituality of African American Women. Inner Traditions International, 2001.

Hurston, Zora Neale. “Characteristics of Negro Expression (1934).” Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present, edited by Angelyn Mitchell, Duke University Press, 1994, pp. 79-94, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1134fjj.12.

Mills, Dana. Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries. Manchester University Press, 2016.

Walker, Alice. “Reaping What We Sow: A Conversation with Pulitzer Prize Winner Alice Walker.” Youtube, uploaded by UC Berkeley Events, 15 February 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TI6xlrCnAO8.